|

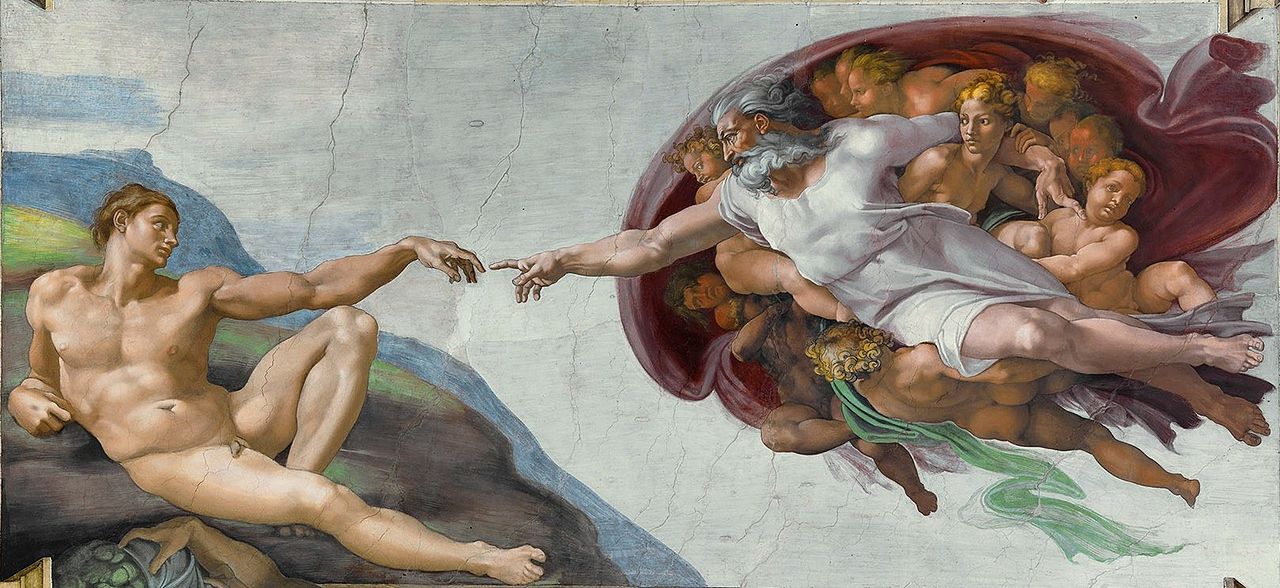

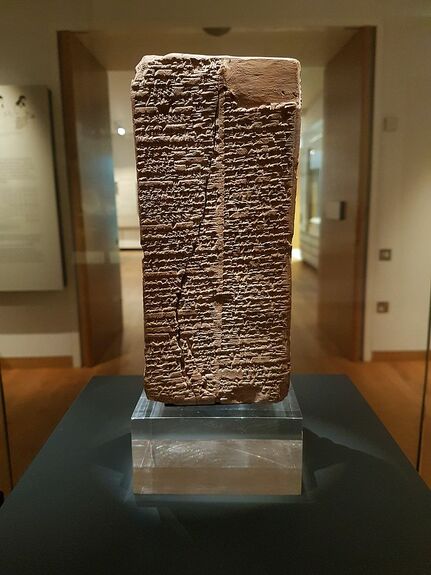

A section of the Sistine Chapel ceiling featuring Adam and scenes throughout Genesis and the Bible. When someone, whether a believer or passive reader of ancient literature, picks up a Bible to read its contents, they will naturally turn to the first page being that it is the beginning of the story. They may be very interested in the first three chapters as it introduces God, characters such as Adam, Eve, the serpent, and their sons, Cain and Abel. But shortly after these brief stories the reader is thrust into a lengthy genealogy beginning with Adam, and his descendants of hard to pronounce and exotic names. This list continues through the course of Genesis, pausing only for key players in the list. One is therefore tempted (like I often was) to skim (or skip) over majority of this list of names to get back to the action. However, could this list of names, years and descendants contain meaning, give life to the text, and provide lessons to the reader? Can this genealogy give any insight to those of us, removed by time and space and perhaps supply a glimpse into the world of Genesis? Can it actually be a valuable part of the narrative involving YHWH and his people? This post will focus on the Generations of Adam throughout Genesis and use a text discovered by archaeology in order to glean a better understanding of this mysterious genre. Genesis and the Sumerian Kings List There are many genealogical lists discovered by archaeology but most fall along the category of a “Kings List.” These lists are used in identifying each king within a dynasty and its purpose is usually to authenticate a particular king in power as the true successor to the throne. We have them from the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt and Mesopotamia. In fact, the kings list, which is often compared with the genealogy in Genesis, is the Sumerian Kings list. WB 444 (Weld-Blundell Prism) This ancient cuneiform tablet was discovered during excavations at Nippur (modern day Iraq) in the early 1900s by a scholar named Herman Hilprecht. Since then, more kings lists from the Sumerian empire have been discovered but the Weld-Blundell prism in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford is the most complete version. It contains a list of rulers from the antediluvian period (pre-flood era) to the fourteenth rule of the Isin dynasty 1763 – 1754 BC. Several items are of interest about this list:

Lists such as these help historians, archaeologist and scholars to identify dynastic periods and compare these periods with other civilizations to establish a “chronology.” However the problem lies with fragmentary lists, and issues such as those mentioned before with inflated, (and assumed estimated) lengthy reigns of the earliest rulers. When compared to Genesis, the lengthy life spans of Adam and his descendants stand out as a parallel to the Sumerian Kings List as well as the mention of a flood and pre-flood era. It also is important to note that Genesis is also establishing a claim of legitimacy in that the Children of Abraham are direct descendants of Adam and Noah. The term “God of your fathers Abraham, Isaac and Jacob” is, in a sense, a mini-genealogy establishing a divine claim for the Children of Israel. A final note before discussing the genealogy as narrative. This list shows that the style and form of the genealogy of Genesis has its roots in Mesopotamia (Sumer is one of the oldest known civilizations by archaeology circa 4500-1900 BC) and this fact alone can provide legitimacy as to the “ancientness” of the Genesis text. Genealogy as Narrative After the events of Creation and The Fall, the author of Genesis focuses on giving an extensive list of generations and their families. The formula that is portrayed is thus: “_(Father Name)_ lived _#_ of years, he fathered _(Son Name)_. _(Father Name)_ lived after he had fathered _(Son Name)_ _#_ of years and had other sons and daughters. Thus all the days that _(Father Name)_ lived were _#_ years, and he died.” The formula stays mostly consistent with the exception of a few names worth mentioning. Narratively speaking, the authors of the Bible often times use repetition as well as grammar and syntax in order to emphasize a particular person or theological point trying to be made. As readers of the Bible it is important to note that these techniques beg the question as to their purpose for such a change or repetition. The authors not only convey a message through the actual words on the page but by the form of the text and arrangement of those words. The genealogies in Genesis are a good example of this. In Genesis we are given a list of names describing a lengthy lifespan for those in the pre-flood period along with mention of the amount of children they have at a particular year. The reason for the information of each man concerning the amount of years one had lived until they began to father children, pertains to the command made earlier to Adam and Even to “be fruitful and multiply” in Genesis 1:28. The author is letting the audience know that this particular person is mentioned in the genealogy because they obeyed the command to have children. In this case, the repetition was to be noted and this common denominator can be found amongst all mentioned. More importantly, of those mentioned in this list of names are those of whom do not fit the formula. The first name on this list that strays from the formula is of a man named Enoch. Gen 5:21-23 says, “When Enoch had lived 65 years, he fathered Methuselah. Enoch walked with God after he fathered Methuselah 300 years and had other sons and daughters. Thus all the days of Enoch were 365 years.” "God took Enoch" illustrated by Gerard Hoet (1648–1733) and others, and published by P. de Hondt in The Hague; image courtesy Bizzell Bible Collection, University of Oklahoma Libraries Majority of these words fit the patterned formula however, verse 23 does not end with “and he died.” Instead, we are given a pause and are told in verse 24, “Enoch walked with God, and he was not, for God took him.” This may seem like a minor divergence from the formula but it is one that should be noted, especially since the list continues right back into its formula in verse 25 with Methuselah. This should beg the question from the reader as to what happened to Enoch and why the abrupt change? Shortly after mention of Enoch, the author decides to give a side story describing the events of a man named Noah and of a great Flood, which covers the whole earth (more on Flood literature in the ANE next month). The story of Noah describes his life and faithfulness in God as he was, the Bible claims, the only righteous man in the world. God is essentially going to start again with humanity from Noah’s family rather than letting the wickedness of man continue on the earth (Gen 6:5-8). The preparation for this event, the event itself and its aftermath take up the bulk of the story. When the story is over, the genealogical formula continues in Genesis 9:28 “All the days of Noah were 950 years and he died.” Immediately following this statement, the text picks right back up with another genealogy following the lineage of Noah however, the author becomes less concerned with mentioning the number of years each man lived and seems more concerned with the territory in which they inhabited. This continues until the mention of the Tower of Babel. After the author directs the attention of the tower and its creation, he shifts back to the original pattern as the beginning of the genealogy saying in 11:10 “These are the generations of…” A similar formula appears: “When _(Father Name)_ lived _#_ of years he fathered _(Son Name)_. And _(Father Name)_ lived after he fathered _(Son Name)_ _#_ years and had other sons and daughters.” The rest of Genesis then follow the events of Abraham and his descendants, Isaac, Jacob/Israel and Joseph. A portion of Dead Sea Scroll which mentions Noah. It is intriguing to see whom the text focuses on as opposed to who the text glosses over. The book of Genesis can been view as one large genealogy beginning with Adam ending until Joseph before the events of the Exodus. Purely looking at these genealogies in a narrative light, one can see that the author is clearly emphasizing certain people within the list on account of their faithfulness to YHWH.

Enoch is singled out and his story is different from the others because in verse 1:24 he was said to have “walked with God” therefore he was taken, and the author does not inform the reader of his death. A similar break occurs with Noah and his “walk with God.” The text is careful to mention Noah’s faithfulness and that he is the only righteous man on the earth. However, the reader is given an abrupt ending to Noah's story immediately after the incident involving his drunkenness and his son’s sin (Gen 9:20-25). The very next thing that happens to Noah is the end of the genealogical formula “All the days of Noah were 950 years, and he died.” The text then dives back in to the genealogy until mention of another man who walks by faith, called Abram. After a careful reading one can see that names that stray from the formula, were meant to be emphasized and a simple theological deduction arises:

This seems like a simple concept but the logic is played out beautifully within the pages of Genesis. Therefore, there are lessons and valuable insights to be gained among these lists of names, which are placed carefully within the text for a reason. As mentioned before, the author(s) skillfully weaved this text together and not only teach its reader using the words on the page but with the form and arrangement of the text itself. Next month my post will focus on the Flood in Genesis compared to other flood literature in the ANE. For further reading: Hallow, W. W. 1963 The Sumerian King List. AS 11. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Sailhamer, John. The Pentateuch as Narrative (Zondervan, 1992).

2 Comments

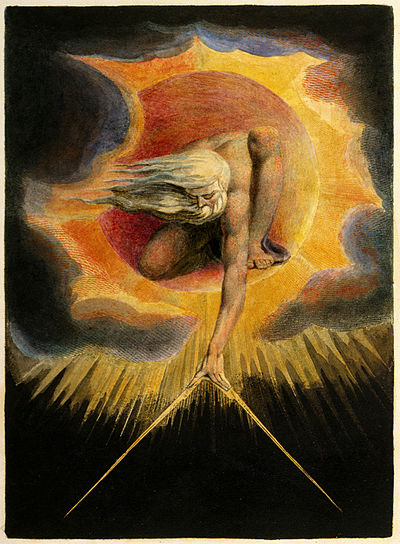

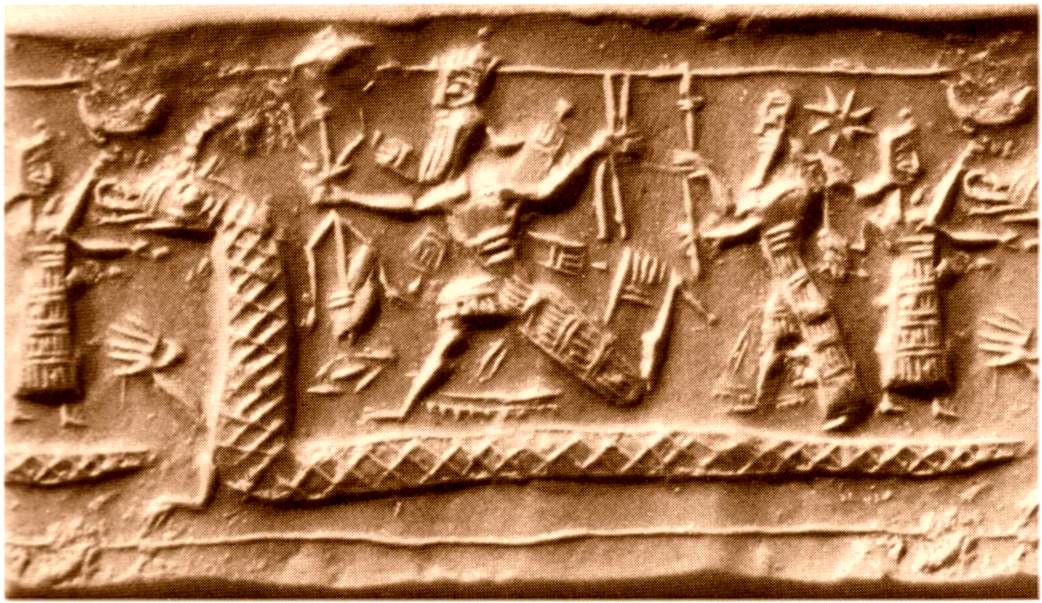

The Ancient of Days (William Blake 1794) Genesis 1 begins with creation ex nihilo or creation “out of nothing.” YHWH from no frame of reference appears to manifest all matter in the universe simply by speaking and thus his words become the physical reality for his presence to dwell. In the creation narrative, Chapter 1 gives a day by day creation account of the 6 days of God’s work followed by chapter 2:1-3 of a seventh day of completion where God rests to admire his work. 2:4 picks back up on the 6th day giving a detailed account of the creation of man, God’s favorite work amongst his creation. This section begins with the formula “these are the generations,” signifying that the book is taking a different direction. Instead of solely focusing on a macro-level of Creation, the author wants to focus on a particular aspect of creation and the relationship of God with mankind. This will eventually lead to the lineage of a specific family through its patriarch, Abraham, from whom will father a great nation that will bless the world. This is common way of story telling in which one begins very general to very specific. The Creation narrative literally is “setting the stage” for God to act in order for the grand drama to unfold. Shortly after, in chapter three, the conflict is introduced and the first antagonist, the serpent, appears to tempt God’s perfect creation. His goal: to change order into chaos. The event of creation takes place within six days (Heb yom). They are outlined as this: Day 1: Creation of Light, Night and Day Day 2: Creation of the Heavens (expanse, Hebrew: raqia) Day 3: Creation of Land and Vegetation Day 4: Stars, Sun and Moon. Day 5: Sea Creatures and Birds Day 6: Land Animals and Mankind Day 7: Sabbath, God finished his Work and Rested Chapter 2 verse 5 gives exposition as to the creation of Man which happened on the sixth day. Critics of the Bible have often said that the Bible is contradicting itself or using two separate sources because of the discontinuity of these two chapters. However, the very same thing happens in Genesis chapter 1:1-2. The author says God created the Heavens and the Earth however, the text later informs the reader that the heavens and the earth was not created until Day 2 and Day 3. This means the author gives a summery statement “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth” then in verse 3 informs the reader of how God accomplished this in the day-by-day formula finishing each day with the proclamation "and it was so" or “and God saw that it was good.” Now, this passage along with other passages within the Bible has been juxtaposed with other ancient literary works such as texts from Mesopotamia, the Levant (Modern Day Israel/Palestine Syria and Lebanon) and Egypt. For the essence of time and length, I will focus on one specific creation myth, the Babylonian Enuma Elish, by giving a brief summery and showing where the two texts are similar and how they are different. I have focused on this one text because it is the one, which scholars assume, share the most themes, words and style with the Bible amongst other ancient Near Eastern epics.  Marduk and the Dragon Enuma Elish also known as the “Babylonian Creation Myth” focuses on the Babylonian god, Marduk and his ascension to prominence in Mesopotamian society. Although Tablets I-VII were recorded relatively late (circa 7th Century BCE discovered at the Library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh along with another famous work, the Epic of Gilgamesh) it supplies traditions of the older creation myths. Therefore, Enuma Elish is not the only Mesopotamia creation myth as there are many creation texts have been discovered. This one in particular is of the most complete and best used for comparative study. The outline of this epic is as follows: Tablet I: Apsu (god of fresh water) and Tiamat (goddess of salt water) were the primordial gods whom created the lesser gods. Apsu became annoyed with the noise of his children and planned to kill them. Tiamat, however put a stop to the plan. The younger gods heard about the plan, slew Apsu and angered Tiamat. Tiamat in response created eleven creatures (monsters) to do battle with the gods. Lesser gods Ea and Damika then created Marduk as a hero god to do battle with the eleven monsters and defeat Tiamat. Tablet 2: Marduk receives his mission to do battle with Tiamat under the condition that if he succeeds, he will become the supreme god of the world. Tablet 3: Marduk travels to the other gods in order to contract them into his supremacy if he wins his battle with Tiamat. Tablet 4: Marduk does battle with Tiamat and uses his power of controlling the four winds to trap her. He uses his net, which was a gift from the god Anu, and sends an arrow through her heart, killing Tiamat. He captures the remaining monsters in his net, and then smashes Tiamat’s head with a mace. He splits her body in half, and one of the halves he makes a sky which will be the home for the gods, Anu, Enlil and Ea. Tablet 5: Marduk makes the stars in the skies (which are supposed to be likeness of the gods), created night and day, and the moon. He also created clouds to send rain to the earth and collect on the ground forming the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Tablet 6: Marduk uses mud of the earth and the blood of the god Qingu to create mankind to serve the gods in order that the gods may rest. Marduk then creates a hierarchy for the gods with Marduk at the top of the pantheon and they construct the city of Babylon along with its temple, Esagila as a Temple for Marduk. Tablet 7: This is a list of Marduk’ s fifty names and titles announcing his supremacy. After reading the story, and in the brief outline I have given, it is perhaps a wonder why the two texts are compared at all. Naturally, there are similar themes shared in both Enuma Elish and the Bible, but what is more striking is the differences one encounters in the two texts. Most notably are the story and clear purpose of both texts. The Biblical Text, as mentioned above focuses a very brief creation account elevating Yahweh as the sole maker of the heavens and the earth by a process of step by step development in order to set the stage for the drama to occur. On the other hand, Enuma Elish seeks to elevate Marduk and the creation account is a mere afterthought after the divine drama has already taken place. The similarities are present and they should not be avoided. These similarities are as follows: 1. Primeval chaos 2. Number of days in creation (seven) 3. Creation of light 4. The firmament (similar Akkadian word to the Hebrew, raqia) 5. Dry land 6. A creation of man 7. God(s) resting Cylinder seal impression depicting Marduk (middle figure) and Tiamat as the Serpent (dragon) Years ago, scholars used the Enuma Elish account to state the direct influence and adaptation of the myth by the author(s) of the book of Genesis. Today this idea is still somewhat shared by majority of scholars however, they are quick to note the differences such as polytheism versus monotheism, as well as a lack of the monsters and battles in the Genesis text as opposed to the Babylonian creation myth. These similarities are now seen mostly as “common ancient Near Eastern religious parallels” rather than influences. This idea (of cultural parallels) is a very different concept as opposed to direct influence of one text upon another. John Oswalt describes it in a very relatable way:

“The same thing is true in the case of many other supposed identical parallels. If one merely lists the characteristics of a human being and a dog, for instance (one nose, two eyes, two ears, hair, circulatory system, etc.) one will certainly conclude the two are essentially identical. However, if you actually put the two side by side, you will reach a very different conclusion.” (Oswalt 2009: 100) In this way, there does appear to be some themes and conflicts that are shared amongst the contemporaneous cultures which speak to their current reality. No doubt we have the same thing happening today in various mediums such as television, movies, music in which artists address a specific political, environmental or geographical climate. However, the way in which they perceive and express these ideals are various. If we attempt what Oswalt states, by putting the two myths side by side, we can appreciate the world of the ancient Near East and gain a better grasp as to the themes that are revealed through these types of literature. Simply let the myths be what they are and glean the ethical, political and historical information of each text. They both tell us something about the ancient world as well as ourselves. Arguments about influence based off of our own presuppositions take away the power and relevancy from both texts. The Bible had it own agenda, in declaring Yahweh as the creator of universe. It does so in its own way clearly separating itself from the other religions and cultures. Next month I will address the Flood epic and the other literature(s) with similar mythologies involving a deluge. Please let me know what you think in the comments and supply your own insights and of course, feel free to ask questions! Bibliography for further reading. The full text of the Babylonian Epic of Creation can be found here. Ehrilich, Carl. From an Ancient Land: An Introduction to Ancient Near Eastern Literature. Roman and Littlefield Publishers. Lanham, MD. 2009. Hays, Christopher. Hidden Riches: A Sourcebook for the Comparative Study of the Hebrew Bible and Ancient Near East. John Knox Press. Louisville, KY. 2014. Oswalt, John The Bible Among the Myths. Zondervan, Grand Rapids MI, 2009.  The story of Genesis is familiar to the most of the Western World. Creation and the Fall (Gen 1-3), Cain and Abel (Gen 4:1-16), Noah’s Ark (Gen 6-9), the Tower of Babel (Gen 11:1-9), Sodom and Gomorrah (Gen 19), and the Joseph story (Gen 37-50) are all tales heard in Sunday school and/or referenced in movies, theatre and music. Any curious reader of the Bible has also read these passages because naturally, one prefers to start at the beginning of any great story. It also whets the appetite of human interest because we are all curious as to our origins. Religion seeks to answer questions and fills the gaps in our knowledge to such things beyond our own observable universe. Genesis, first and foremost, is about one thing before it is about anything else: man’s salvation history.* Genesis focuses on 1) introducing the protagonist, God, 2) his creative work of the universe, 3) His favorite work in creating Man, 4) Man’s rejection of God and introduction to the conflict of Sin, and 5) the establishment of Covenant with one family/tribe and how they will assist in the blessing of the nations until order is restored. These next few blog posts will address the tales in Genesis mentioned above. It will require a month or so to research and write a summary of the topics described and provide a bibliography for further research and reading if you so desire. I can also provide more sources on these subjects as well. On the subject of Genesis as Narrative however, Genesis is a literary work of art. It is both simple in its complexity and complex in its simplicity. The author (or authors) intricately and intentionally used a variety of literary techniques that go well beyond “children’s stories.” Those that enjoy it in its original Hebrew no doubt pick up on these techniques during a reading of the text. The use of poetry, prose and even genealogy are all skillfully woven together in this work and everything written is plainly intentional. Critics of the Pentateuch (or Torah, the first five books of the Bible) used to highlight aspects such as repetition used in the Bible as a jumping off point for Source Criticism. They would often condemn the writers and redactors for forgetting that certain words and phrases are mentioned more than once as the redactor compiled and copied the manuscripts. However, we now know that these repetitions (once thought as mistakes) are actually skillful techniques used in a pre-literate, oral society in order to maintain cognitive memory practices in reciting the text to one another. This is a foreign concept to the Western World because we only imagine something as “publishable” or as “proof” when it is written down. There is no such thing as an oral contract in this day in age. We do not trust people by their spoken word, but instead we have to take further legal means by putting things on paper. The concept of a completely “Oral Bible” make us uncomfortable because we view the world with an extremely conflicting paradigm. The language of the Bible was written this way because the words are meant to be recited and memorized. This is why you see repetition of a word or phrase, and in Hebrew you see literary tricks like onomatopoeia and alliteration. These techniques were all used intentionally to help the reader or listener to memorize the passage easier. With this knowledge in mind, one can easily imagine shepherds tending to their flocks in the wilderness, camping out under the stars, and reciting these “tales of old” to their families and companions. Tales they heard and memorized from their fathers and grandfathers about how the stars were placed in the heavens, how a man named Joseph went from a shepherd like them to a Vizier ruling over all of Egypt, and how God will one day return to make the world new again, to be a like a beautiful Garden, where they can have their fill of any tree. The stories were memorized and without the interference of modern day distractions we could possibly accomplish these things as well. The book of Genesis also contains elements of other contemporaneous cultures such as Egypt, Anatolia and Mesopotamia within its language because, naturally, those were the cultures surrounding Ancient Israel in those times. The Joseph story has elements of Egyptian names, cultural references and loan words because the setting of most of the Joseph story takes place in Egypt. If Moses were indeed the writer, being of the Egyptian royal household, then he would be intimate with Egyptian culture and language in order to tell the story correctly. Now, with all of that said, we can now proceed with our theme of “Genesis Among the Myths.” One may have heard of other creation and flood stories from other cultures such as from Mesopotamia and Egypt. From a surface level reading of these texts, one could compare these myths to the Bible and see some assumed similarities. It was important to establish Genesis as narrative in order to better understand the medium in which the text is written in light of other Ancient Near Eastern literary texts. Next month I will address the passage in Genesis 1 and 2 regarding the Creation account. I will attempt to explain what the author is doing with the text and compare it to some other creation accounts in the Ancient Near East. [Disclaimer: I will not be dealing with the issue of literal 6-day creation because, unfortunately (or perhaps fortunately), it is not my area of expertise. I am an archaeologist and biblical scholar, that is more within the discipline of astrophysics.] For further reading in the subject of Genesis as Narrative, please see these books. I highly recommend Robert Alter’s pioneering monograph conveniently entitled The Art of Biblical Narrative. It’s a very readable book and a great introduction to the Bible as a cohesive story. Alter, Robert. The Art of Biblical Narrative (Basic Books, 1981). Fokkelman, J. P. Reading Biblical Narrative (Westminster: John Knox Press, 1999). Long, V. Philips. The Art of Biblical History (Zondervan, 1994). Sailhamer, John. The Pentateuch as Narrative (Zondervan, 1992). *Notice I designate the Bible as “man’s salvation history” rather than defining it as history in our postmodern, western mindset. I already discussed this briefly in my first blog post. View it here. |

Archives

June 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed