|

For some, the summer means school is out for students. Growing up in Florida, it meant going to the beach daily, barbecues, bon-fires and fishing. When one is in the academic discipline of archaeology, summer means: “dig season.” It is true that there are other excavations, which operate outside of the months of May – July, but in the Middle East, summer is the most convenient for students. Field schools are in full swing and archaeological projects either begin and/or pick right up where they left off last year. In this case, Khirbet Safra kicked off its second season in Jordan for 6 weeks (end of May to mid-July). Andrews University has been involved with excavating major sites in Jordan since 1968 led by the renowned archaeologist Sigfried H. Horn. In fact, Tall Hesban Excavations just celebrated its 50th year anniversary of continuous work as apart of the Madaba Plains Project. Two additional excavations at Tall El-Umayri (1984) and Tall Jalul (1992) have also been excavated by Andrews. :::Warning::: Technical, but not too technical, archaeology jargon coming henceforth. All pictures I use in this post are my own (unless specified) and are, by no means, publishable quality. I do this intentionally to protect the integrity of the publication materials** Arial of Khirbet Safra showing the four fields A-D before excavation. Remnants of the wall are visible as are several caves. A modern day, dirt road is also visible and shows, logically, the way one would find accesses into the ancient city. (Picture courtesy: Andrews University)To answer more questions regarding the Iron Age in Transjordan (the ancient, politically correct term for the land in modern-day, Jordan) excavators moved their focus southwest to Khirbet Safra. Some sites in archaeology are called Tells/Talls or Khirbets. A Tell is a mound created over time with layers of ruins and occupations beginning with the most recent occupation on the top and the earliest material culture at the lowest levels. (For a more thorough description of Tell structures check out my previous blog post here.) A khirbet is the designation for a site in which ruins or architecture are exposed prior to any excavation or disturbance to the site. From aerial photographs the khirbet has a clear outer-wall surrounding the circumference of the city, along with an inner wall forming the interior of what is known as a “casemate” – a double reinforced wall structure commonly seen in the Levant. Example of Casemate wall structure at Tel Hazor, Israel. (wikicommons)Initial survey of the site found several different time periods of pottery on the surface ranging from Iron II (10th-6th century BC) to the Byzantine periods (AD 3rd-6th century). Four fields were opened on the four areas of the khirbet -- A, B, C, and D. These fields were strategically placed in order to 1) delineate the casemate (in all fields); 2) expose any remaining gate structure(s) in the north and east of the city (fields C and D); and 3) expose any large, assumed administrative structures in logical locations (Fields A and B). The first season (2018) yielded fine results of pottery and helped establish a better chronology of the site. Two squares were opened in each Field and majority of the squares were finished and closed by the end of the season on account of bedrock laying a meter to a meter and a half under the surface. In most areas, upon the exposed bedrock was a sealed locus of Iron I pottery dating to the 13th Century BC, which was earlier than what the excavators expected since Iron II pottery sherds were collected in the initial 2017 ground survey. The second season, in 2019 was focused primarily on Fields B and D respectively. Field B opened four new squares where a monumental building was discovered abutting the casemate wall to the south. Field D also opened four more squares and discovered several rooms connected to a 13th century gate complex to the city, complete with a threshold stone and stone benches. The gate finding is significant for several reasons since it is a high traffic area for entrancing and exiting the city. Many administrative and legislative processes occur at city gates. For ancient and biblical Parallels, look at texts dealing with events where the elders meet at the city gates to make judgements and form contracts. (Gen 19:1; Deut 25:7; Ruth 4:1, 11; 2 Sam 23:15; 2 Kngs 7:1, 7:17; Prov 31:23; etc). Benches on either side of gate entrance. Fellow archaeologist, Jacob Moody and I are reenacting how elders would discuss legal matters at city gates.Picture of the Gate in Field D looking North. I'm standing in the threshold for scale.A better picture of phasing is appearing and it tells us that the first settlers to Khirbet Safra built a walled town/city upon bedrock, filling in holes and depressions in the bedrock with a red-bricky material in order to make it flat. The site was most likely destroyed at one time as there is a thin ash layer in Fields A and B, most likely caused by an earthquake on account of tectonic/seismic activity frequent along the Jordan River Valley which is a known fault line. There may be evidence of destruction based on the emerging Moabite presence in surrounding ancient towns and cities. Some settlers during the Byzantine period reused the abandoned/destroyed walls in Fields A and B but only had a short period of occupation. Top down view of Field D gate complex facing Southeast. You can see where the holes in the bedrock were filled with a red-bricky material. In the top right corner of the picture is the balk line and surface. Bedrock and Iron Age I surface was barely a meter below topsoil in some areas.For copyright and publication reasons, I will leave any more details about the findings of Khirbet Safra for now. It is a fascinating site which will help answer questions we may have concerning the Transjordan in the Iron Age I. For those interested in Biblical Chronology and archaeology, this is most likely the time period of Joshua and Judges. If geographic information and boundaries in the Bible are accurate then the city of Khirbet Safra lies within ancient Reubenite territory. Next Season we hope to reopen all 4 fields and continue with excavation. Although some questions were answered, more questions are raised. We have yet to find any inscriptional evidence or material culture which shows what kind of people lived at Khirbet Safra, whether they were Moabite, Ammonite or -- dare we say, Israelite? Only time will tell as we press onwards and downwards. Consider joining us next year as we dig into history and uncover the secrets of Khirbet Safra. Khirbet Safra 2018 Dig TeamMembers of the 2019 Dig Team. Forgive me for the poor picture quality until I can find a better dig photo for the 2019 team.I realize a lot of this text can appear as technical, archaeology “mombo-jumbo.” However, these are valuable results that we uncover which help us understand the world that came before us and ultimately tell us something about ourselves. Archaeology is about discovering our intellectual heritage. It is not all working in the hot sun every day. You can see my video in what a typical day in the life of an archaeologist looks like here. When we are not working, we tour exotic sites, eat wonderful Jordanian cuisine and more importantly, form relationships with people who are not much more different that ourselves. Archaeology is an opportunity for building a bond between people of different cultures. It brings together people from all walks of life based on age, ethnicity, language, religion and politics. We coexist and work towards a better understanding of humanity. See my video of our wonderful volunteers and students from last year here. Come join in on the adventure with us next year. You will not regret it.

-Tal

0 Comments

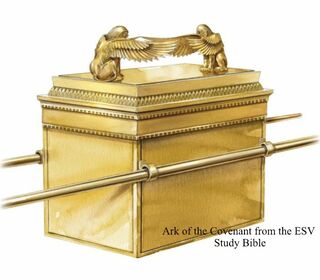

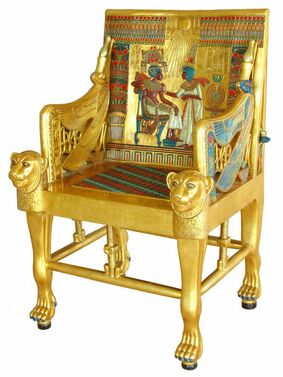

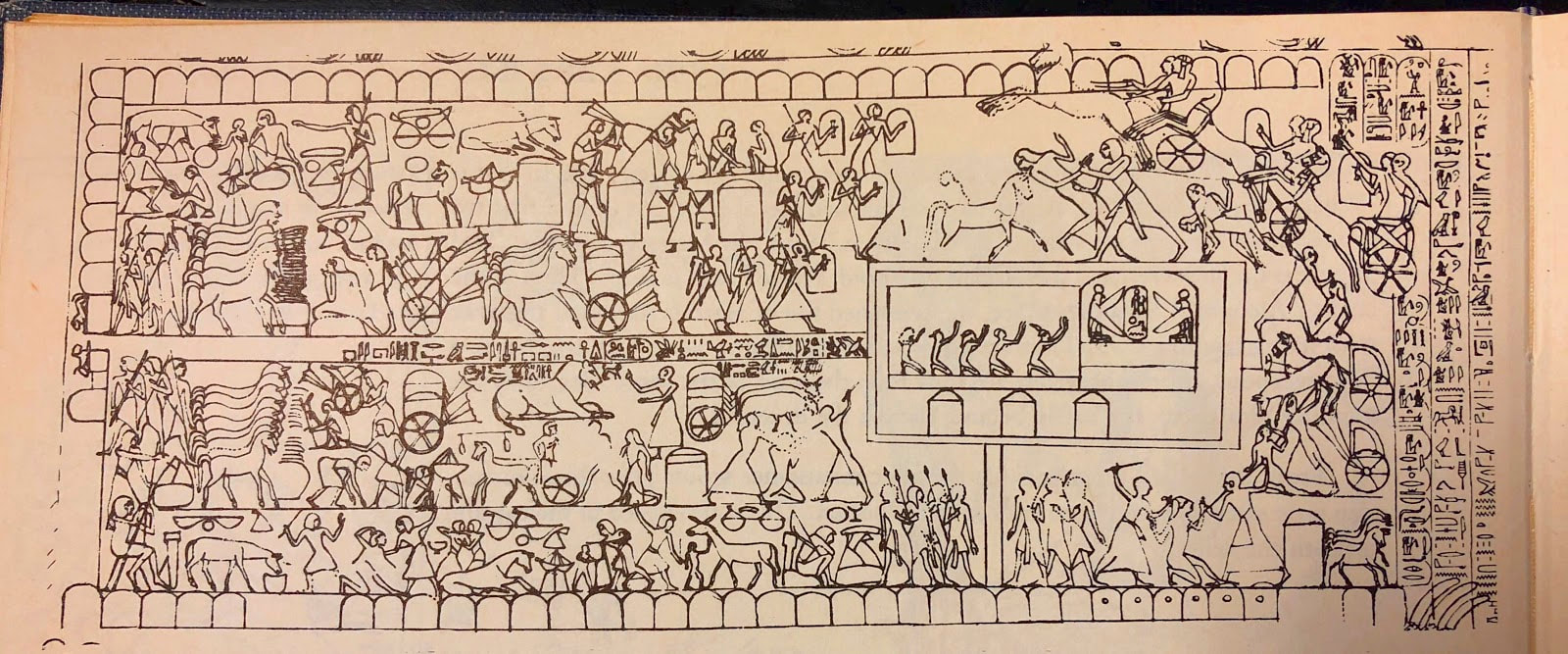

This is the question that typically follows any statement of my particular vocation. More often than not, it is in fact the single most asked question I receive as an archaeologist. Perhaps this post will not give you the answer you were hoping for, but at least to some, I can lay to rest the question that has been on your mind for a long while. 1981 in fact. This is of course, the release of the swashbuckling adventure of Indiana Jones: Raiders of the Lost Ark, which inspired many archaeologists (including myself) and filled them with dreams of traveling the world, fighting Nazis, getting the girl and discovering aliens exist (…maybe we’ll just forget about that last one). If I haven’t lost many of you by now after mentioning last installment of The Crystal Skull, jokes aside, I will attempt in this post to give some history of the Ark, its purpose, and some historical and traditional views on what might have happened to it. The Ark of the Covenant was first created as a result of a commandment by God in the Book of Exodus 37, approximately one year after the events of the exodus while the Israelites were in the Sinai wilderness. It was constructed of Acacia wood, 45 inches longs, 27 inches wide, and 27 inches tall. The chest was then overlaid with gold, bolted with rings for carrying poles and was finally a lid with two solid gold cherubim (angels) figurines facing each other with their wings outstretched toward each other and spread out over the lid. According to the New Testament book of Hebrews 9:4, this iconic relic held three things within its confines: the tablets given to Moses containing the Ten Commandments, the Staff of Aaron which was used in the Plagues as well as the same staff which bloomed signifying that Aaron’s sons would be the priests (Levites) to uphold the Laws of YHWH, and a golden pot of manna collected from the wilderness. The function of the Ark has been debated, however the Bible does mention that it was to contain the “Presence of God." The Hebrew word kepporet seems to indicate that the lid of the Ark functioned as the Throne of God as he is “seated upon the Cherubim” mentioned in Isaiah 37:16 “O LORD of hosts, God of Israel, enthroned above the cherubim, you are the God, you alone, of all the kingdoms of the earth.” This would fit well within its ancient Near Eastern Context if we look at other contemporaneous cultures during the time period of the Late Bronze age such as Egypt and Assyria. Egypt has perhaps two of the best examples of similar throne structures. The first and perhaps most popular is the throne of King Tutankhamen. One can see that there are many animal-like figures which match the description of Cherubim in the ANE (Ancient Near East) as hybrid-winged creatures and symbolize the realm of the gods. In this throne, it can be plainly seen that King Tut was seated upon Cherubim creatures, which represented his protection by angelic beings as well as his place among the gods. Pharaohs in ancient Egypt were essentially the reincarnation of the god Horus. The next example is far more obvious when it comes to the role of the Ark in light of Egyptian religion. This scene is a depiction of Pharaoh Rameses II’s tent structure at Abu Simbul in Egypt. The relief dates to Rameses II’s reign in 1279-1213 BCE and shows a tent structure with the Pharaoh’s throne at the center of the camp. Many have made connections with his military tent to the Tabernacle and its arrangement. Rameses’ throne room has two cherubim with their wings outstretched with his cartouche (the encased name of the Pharaoh in hieroglyphics) between them. It’s a remarkable image that perhaps shows that author of the Exodus is reworking the Tabernacle and throne imagery to show that YHWH, not Pharaoh, is the one worthy of worship.

Therefore, the purpose of the Ark was to be the throne of God, not necessarily that his presence was in the Ark, but rather, seated on top since YHWH was supposed to be the first and only king of the Israelites. This also fits with other passages of the Hebrew Bible which instruct the Israelites to carry the Ark before them as they travel. Majority of the events surrounding the Conquest of Canaan center around the Ark, such as the crossing of the Jordan River in Joshua 3 and the battle of Jericho in Joshua 6:4-15. The Ark was supposed to symbolize the fulfillment of God’s covenant with his people in that they would indeed be given the land promised to them as well as God being the one who would fight Israel’s battles for them. The Ark after this point has a rough history. The Ark was housed in the biblical city of Shiloh (currently being excavated today) until the Philistines capture it (mentioned in 1 Samuel 4:3-11) and was kept for 7 months until its return back to Israelite territory. It was then housed in different cities such as Beth Shemesh (also being excavated today) before being sent to David’s capital in Jerusalem. It was not until Solomon built his Temple that the Ark had a final resting place for a hundred years or so. The Ark was returned to the Temple during Josiah’s reign (7th century BCE) and the Bible is not clear why or who removed it from the Temple (2 Kings 21-23) prior to this event. After the Ark was established in the Temple of Solomon, it plays a pivotal role in the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippor (The Day of Atonement). On this special day, only the high priest was allowed into the Holy of Holies on behalf of the people of Israel. Their job was to sprinkle the blood of an unblemished lamb upon the Ark, or the throne of God. This symbolized the price for the sins of Israel being atoned by this act. This holiday occurs once a year and was the only time anyone was allowed behind the curtain into the Holy of Holies. This is when the location of the Ark becomes murky. After the destruction of the Temple in 586 BCE it is implied that the Babylonians might have been the ones to raid the temple and take the Ark with them back to Babylon as plunder along with the Judean exiles. In the book of 1 Esdras (an ancient Greek form of the book of Ezra), it claims that vessels of the Ark were taken with them but not the Ark itself (1 Esdras 1:54). There is a possibility it could have been taken with the Babylonians, however it is unknown. 2 Maccabees 2:4-10, however also states that the prophet Jeremiah, knowing of the oncoming campaign of Nebuchadnezzar and his army of Babylonians, took the Ark and hid at the site of Moses' resting place on Mt. Nebo (in modern day Jordan) until “the time that God should gather his people again together." There is the theory that the Pharaoh Shishak (most likely Shoshenq I of the 22nd Dynasty of Egypt) mentioned in the Bible in 1 Kings 11:40, 14:25 and 2 Chronicles 12:2-9, took the Ark of the Covenant during one of his campaigns through the Levant. He raided the temple of Solomon and took its riches back to Egypt. No doubt this would have included the Ark of the Covenant. However, there is no written sources whether Egyptian, or Biblical that can confirm this theory. A version of this theory is of course used in the Raiders of the Lost Ark film. If the Ark still exists and survived either campaigns of the Egyptians or Babylonians, there are several places which claim to have the sacred box. The most popular among these locations is the Chapel of the Tablet at the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion in Axum, possession of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. Only one priest is allowed in the building where the Ark is held. A popular book written by British author Graham Hancock, The Sign and the Seal: The Quest for the Lost Ark of the Covenant also proposes this location as the final resting place for the ark. However there is little historical merit to his claims and most scholars do not hold to these views or claims. The search for the Ark is a popular topic and inspires many with dreams of adventure, intrigue and conspiracy. However, there is not much historical and archaeological data that give any evidence as to what happened to an object such as this. More than likely (and this is my own opinion) that the empires of Egypt and Assyria would have little use for a sacred box containing some tablets, a staff and a pot of flowers. They would simply have stripped the gold from its wood and added it amongst their booty. I realize this is an anticlimactic end to such an influential and symbolic object of the Bible, however Jewish religion continued on. The Holy of Holies in Zerubbabel’s Temple and in Herod’s Temple was void of the Ark of the Covenant although the presence of God was supposed to still be dwelling behind the curtain; the curtain’s purpose being to separate the righteousness of God with the sinful world. The Jews of the Second Temple Period clearly did not feel the need to remake another Ark and were satisfied with the vacancy in its place. On Yom Kippur the blood of the lamb, that was to be sprinkled on the Ark, was instead sprinkled on the empty place where the Ark sat, most likely a reminder of the sins of the people, which led to their sacred relic being taken from them. Therefore, Jewish life and ritual continued on. Perhaps if the ancient Jews were willing to let the Ark be lost, we should too. |

Archives

June 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed