|

Summer Excavations are in the books, a new semester has started and publications are being written. In the meantime, I figured I’d answer one of my “frequently asked questions" with my next post. A question I am often asked is: “how does one choose a site to dig?” Archaeology as a discipline began in the 17th and 18th centuries. The methodology used today was developed in mid 1800’s by a famous Egyptologist, William Flinders Petrie also known as the “Father of Archaeology.” He developed a dating technique known as Ceramic Typology (for an explanation of this, see video “A Day in the Life of an Archaeologist”). This began what was known as the “Golden Age” of archaeology in which people began seriously considering this discipline as a profession. Other methodological techniques such as the Wheeler-Kenyon method came out of this age (setting up sites in a grid system and excavating stratigraphically based on the architecture and material culture), which we still implement today and even still might be the preferred method of excavation. This introduction to archaeology as a scientific/academic discipline helped shape the way we understand the evolution of human civilization in an even bigger picture within anthropology. The Wheeler-Kenyon Method maps the site out into a grid of 5x5 meter squares for excavating. A one-meter buffer or "balk" in between each square are used to keep track of the changes in layers in order to have complete, three dimensional control of the area. Assigned to each square is a supervisor tasked with taking meticulous notes of not only artifacts which may pop up, but also architecture, soil color and consistency, measurements, and other miscellaneous data. Implementing the Wheeler-Kenyon methods to Khribet Safra Within this understanding of anthropology, in which one chooses to excavate a site, there are many factors that come into play before one even puts spade to dirt. Text and oral tradition play a role in choosing a site, however before one attributes these indicators to a site one has to consult the basic needs of any human culture. I will name four which are, including, but not limited to:

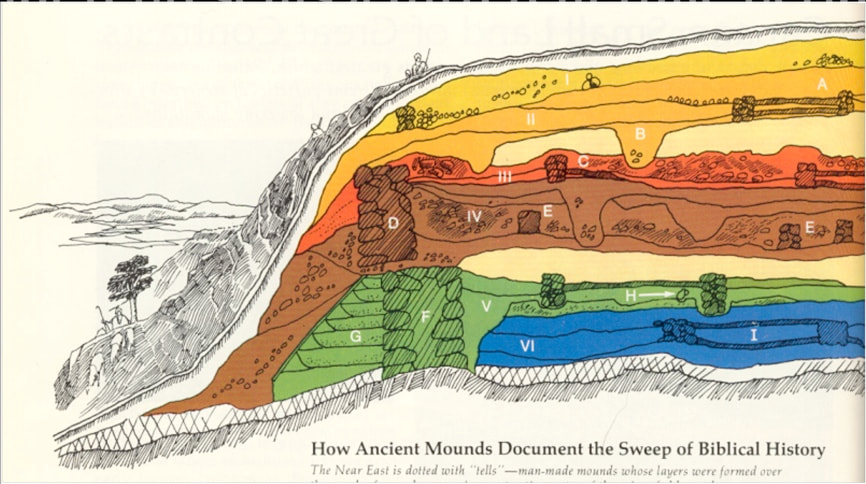

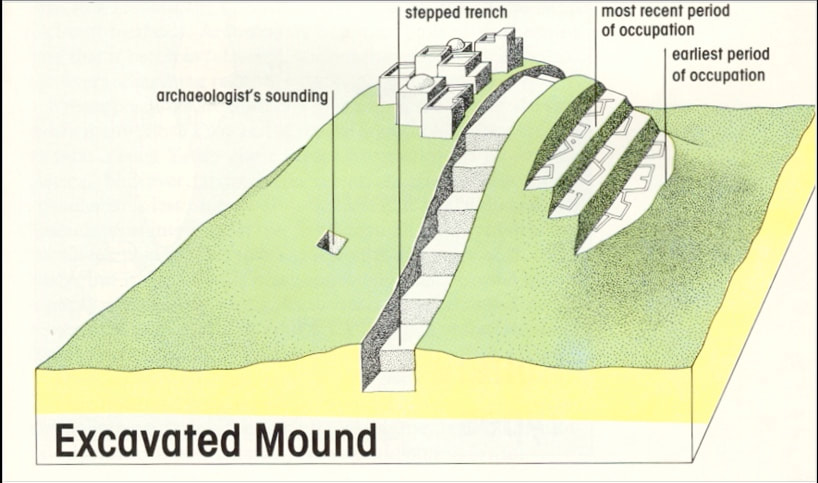

Aside from Wifi (which would no doubt be a necessity for most in this day in age) these four factors must be present when a site is in consideration. This can all be determined by viewing aerial images and maps (both modern and ancient). If one of these factors are not present, then an explanation is needed in order to show how this factor is compensated. For example: if there is no clear water system such as a river, lake or spring nearby, then how did the ancient people living at the site gain access to water? Now, there are clearly exceptions to this rule for not every site is easily explainable. However, majority of the time, these factors are available and they are somewhat universally applied to sites all over the world. The ancient fortress of Masada. Archaeologist are still perplexed as to how the ancient peoples had access to water on a mountain in the middle of the Judean Desert. Conveniently enough, in the Near East, this is one more factor that helps in identifying a site for excavation, this is a structure known as a “Tel” (Arabic: “Tall”). The word Tel means, “ruin” and it is a man-made mound with layers and layers of human settlements created over centuries. You may have heard some sites referred to as “tels” such as Tel Abel Beth-Ma’acah, Tel Miggiddo, Tel Hazor, or Tel Azekah. These are in reference to the site as an ancient city or town with multiple occupations over the course of human history. This is of course compared to what is also known as a “khirbet,” which is a site where there are exposed ruins on the surface. The excavation I am currently involved with is known as Khirbet Safra, which is not a tel structure. Before adequate techniques of archaeology were put into practice, trench archaeology was applied to some sites, which it was precisely as it sounds. Past archaeologists would dig a large trench in the middle of the tel, like slicing off a piece of cake, in order to see the layers in relationship to the site. As one can imagine this was a horrible method as it destroys a considerable percentage of the site. When the Wheeler-Kenyon method was adapted and applied, it was a slower process, but much more controlled and yielded better results. After the basics of human needs are addressed comes the fun part of choosing a site. This is where one will look at textual evidence and oral traditions in order to determine if a site is worth excavating and also helps judge the importance of a site. Countless surveys done by explorers and cartographers have identified sites that are yet to be excavated today. The modern names of some sites are typically given by local neighbors and settlers. This is what is referred to as an “oral tradition” of the site. Sometimes even the modern name of a site will contain traces of the ancient name in it such as Tall Heshbon in Jordan (ancient Hesban in the biblical text). Other sites like Tel es-Sultan have been identified as the ancient biblical city of Jericho based off of geographic information from textual sources such as the Hebrew Bible and ancient maps, as well as the oral tradition of the surrounding settlements of the site in question.

Choosing a site is a process and should not be taken lightly. It is as much of a science as the method of excavation applied to a site. A lot of care is taken into choosing a site because once one has put spade-to-dirt, the site will never be the same way again. Archaeology as a discipline is destructive by nature. Excavators have the ethical responsibility of man’s intellectual heritage to uncover what lies beneath one layer at a time. Let me know what you think in the comments! If there are other questions you may want to ask and archaeologist leave it in the comments below. -Tal

2 Comments

|

Archives

June 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed