|

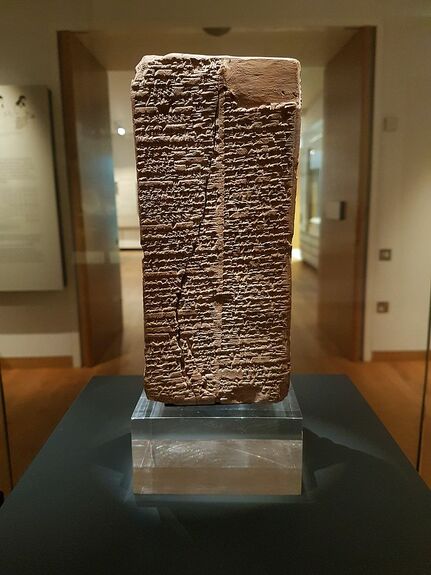

A section of the Sistine Chapel ceiling featuring Adam and scenes throughout Genesis and the Bible. When someone, whether a believer or passive reader of ancient literature, picks up a Bible to read its contents, they will naturally turn to the first page being that it is the beginning of the story. They may be very interested in the first three chapters as it introduces God, characters such as Adam, Eve, the serpent, and their sons, Cain and Abel. But shortly after these brief stories the reader is thrust into a lengthy genealogy beginning with Adam, and his descendants of hard to pronounce and exotic names. This list continues through the course of Genesis, pausing only for key players in the list. One is therefore tempted (like I often was) to skim (or skip) over majority of this list of names to get back to the action. However, could this list of names, years and descendants contain meaning, give life to the text, and provide lessons to the reader? Can this genealogy give any insight to those of us, removed by time and space and perhaps supply a glimpse into the world of Genesis? Can it actually be a valuable part of the narrative involving YHWH and his people? This post will focus on the Generations of Adam throughout Genesis and use a text discovered by archaeology in order to glean a better understanding of this mysterious genre. Genesis and the Sumerian Kings List There are many genealogical lists discovered by archaeology but most fall along the category of a “Kings List.” These lists are used in identifying each king within a dynasty and its purpose is usually to authenticate a particular king in power as the true successor to the throne. We have them from the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt and Mesopotamia. In fact, the kings list, which is often compared with the genealogy in Genesis, is the Sumerian Kings list. WB 444 (Weld-Blundell Prism) This ancient cuneiform tablet was discovered during excavations at Nippur (modern day Iraq) in the early 1900s by a scholar named Herman Hilprecht. Since then, more kings lists from the Sumerian empire have been discovered but the Weld-Blundell prism in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford is the most complete version. It contains a list of rulers from the antediluvian period (pre-flood era) to the fourteenth rule of the Isin dynasty 1763 – 1754 BC. Several items are of interest about this list:

Lists such as these help historians, archaeologist and scholars to identify dynastic periods and compare these periods with other civilizations to establish a “chronology.” However the problem lies with fragmentary lists, and issues such as those mentioned before with inflated, (and assumed estimated) lengthy reigns of the earliest rulers. When compared to Genesis, the lengthy life spans of Adam and his descendants stand out as a parallel to the Sumerian Kings List as well as the mention of a flood and pre-flood era. It also is important to note that Genesis is also establishing a claim of legitimacy in that the Children of Abraham are direct descendants of Adam and Noah. The term “God of your fathers Abraham, Isaac and Jacob” is, in a sense, a mini-genealogy establishing a divine claim for the Children of Israel. A final note before discussing the genealogy as narrative. This list shows that the style and form of the genealogy of Genesis has its roots in Mesopotamia (Sumer is one of the oldest known civilizations by archaeology circa 4500-1900 BC) and this fact alone can provide legitimacy as to the “ancientness” of the Genesis text. Genealogy as Narrative After the events of Creation and The Fall, the author of Genesis focuses on giving an extensive list of generations and their families. The formula that is portrayed is thus: “_(Father Name)_ lived _#_ of years, he fathered _(Son Name)_. _(Father Name)_ lived after he had fathered _(Son Name)_ _#_ of years and had other sons and daughters. Thus all the days that _(Father Name)_ lived were _#_ years, and he died.” The formula stays mostly consistent with the exception of a few names worth mentioning. Narratively speaking, the authors of the Bible often times use repetition as well as grammar and syntax in order to emphasize a particular person or theological point trying to be made. As readers of the Bible it is important to note that these techniques beg the question as to their purpose for such a change or repetition. The authors not only convey a message through the actual words on the page but by the form of the text and arrangement of those words. The genealogies in Genesis are a good example of this. In Genesis we are given a list of names describing a lengthy lifespan for those in the pre-flood period along with mention of the amount of children they have at a particular year. The reason for the information of each man concerning the amount of years one had lived until they began to father children, pertains to the command made earlier to Adam and Even to “be fruitful and multiply” in Genesis 1:28. The author is letting the audience know that this particular person is mentioned in the genealogy because they obeyed the command to have children. In this case, the repetition was to be noted and this common denominator can be found amongst all mentioned. More importantly, of those mentioned in this list of names are those of whom do not fit the formula. The first name on this list that strays from the formula is of a man named Enoch. Gen 5:21-23 says, “When Enoch had lived 65 years, he fathered Methuselah. Enoch walked with God after he fathered Methuselah 300 years and had other sons and daughters. Thus all the days of Enoch were 365 years.” "God took Enoch" illustrated by Gerard Hoet (1648–1733) and others, and published by P. de Hondt in The Hague; image courtesy Bizzell Bible Collection, University of Oklahoma Libraries Majority of these words fit the patterned formula however, verse 23 does not end with “and he died.” Instead, we are given a pause and are told in verse 24, “Enoch walked with God, and he was not, for God took him.” This may seem like a minor divergence from the formula but it is one that should be noted, especially since the list continues right back into its formula in verse 25 with Methuselah. This should beg the question from the reader as to what happened to Enoch and why the abrupt change? Shortly after mention of Enoch, the author decides to give a side story describing the events of a man named Noah and of a great Flood, which covers the whole earth (more on Flood literature in the ANE next month). The story of Noah describes his life and faithfulness in God as he was, the Bible claims, the only righteous man in the world. God is essentially going to start again with humanity from Noah’s family rather than letting the wickedness of man continue on the earth (Gen 6:5-8). The preparation for this event, the event itself and its aftermath take up the bulk of the story. When the story is over, the genealogical formula continues in Genesis 9:28 “All the days of Noah were 950 years and he died.” Immediately following this statement, the text picks right back up with another genealogy following the lineage of Noah however, the author becomes less concerned with mentioning the number of years each man lived and seems more concerned with the territory in which they inhabited. This continues until the mention of the Tower of Babel. After the author directs the attention of the tower and its creation, he shifts back to the original pattern as the beginning of the genealogy saying in 11:10 “These are the generations of…” A similar formula appears: “When _(Father Name)_ lived _#_ of years he fathered _(Son Name)_. And _(Father Name)_ lived after he fathered _(Son Name)_ _#_ years and had other sons and daughters.” The rest of Genesis then follow the events of Abraham and his descendants, Isaac, Jacob/Israel and Joseph. A portion of Dead Sea Scroll which mentions Noah. It is intriguing to see whom the text focuses on as opposed to who the text glosses over. The book of Genesis can been view as one large genealogy beginning with Adam ending until Joseph before the events of the Exodus. Purely looking at these genealogies in a narrative light, one can see that the author is clearly emphasizing certain people within the list on account of their faithfulness to YHWH.

Enoch is singled out and his story is different from the others because in verse 1:24 he was said to have “walked with God” therefore he was taken, and the author does not inform the reader of his death. A similar break occurs with Noah and his “walk with God.” The text is careful to mention Noah’s faithfulness and that he is the only righteous man on the earth. However, the reader is given an abrupt ending to Noah's story immediately after the incident involving his drunkenness and his son’s sin (Gen 9:20-25). The very next thing that happens to Noah is the end of the genealogical formula “All the days of Noah were 950 years, and he died.” The text then dives back in to the genealogy until mention of another man who walks by faith, called Abram. After a careful reading one can see that names that stray from the formula, were meant to be emphasized and a simple theological deduction arises:

This seems like a simple concept but the logic is played out beautifully within the pages of Genesis. Therefore, there are lessons and valuable insights to be gained among these lists of names, which are placed carefully within the text for a reason. As mentioned before, the author(s) skillfully weaved this text together and not only teach its reader using the words on the page but with the form and arrangement of the text itself. Next month my post will focus on the Flood in Genesis compared to other flood literature in the ANE. For further reading: Hallow, W. W. 1963 The Sumerian King List. AS 11. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Sailhamer, John. The Pentateuch as Narrative (Zondervan, 1992).

2 Comments

|

Archives

June 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed