|

November for academics is perhaps one of the most stressful months of the year. Project deadlines are due, professional meetings take place (SBL, ASOR, ETS) and preparing for finals is on the horizon. Contrary to what you may believe, I have always said that finals week and the week before is actually quite pleasant. By this time I have typically wrapped up all of my projects and papers and I only have to focus on finals. For this semester, I have gotten the chance to try my hand at teaching some courses in Andrews University's seminary. One course in particular is called "Egypt and the Bible." Next semester, I will most likely post something that pertains to material and research I have been doing for this class, but for this month, I wanted to address a popular subject in Biblical Studies: the Dead Sea Scrolls

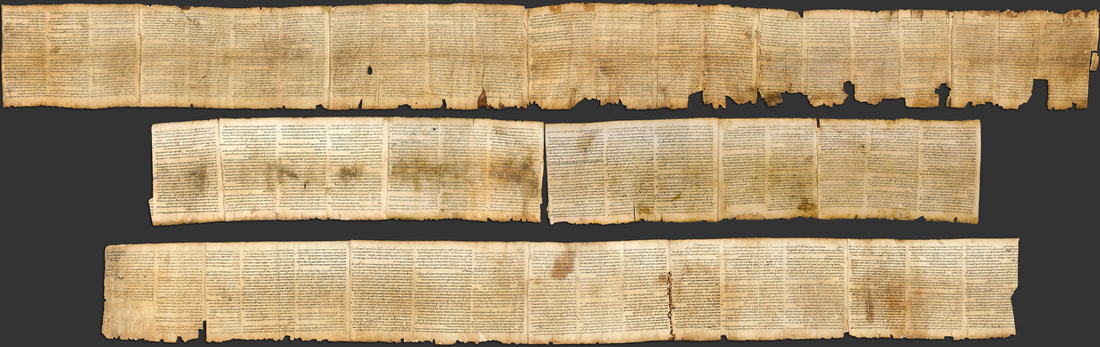

Working with the Horn Archaeological Museum, I get the opportunity to work aside great scholars and archaeologists. One of my earlier posts this year was on the subject of Zoroastrianism and Critical Scholarship, in which I was able to present at our Horn Lectureship Series (see post below). This Fall we were able to invite Dr. James VanderKam from the University of Notre Dame. He is an expert on the Dead Sea Scrolls (from now on DSS) and has been involved with DSS studies for the past few decades. Many people no doubt have heard of the discovery of these ancient texts, and know that they have some relationship to the Bible we have today, but how exactly are the two connected? How do they give us any reliability in the Bibles we have on our shelves and on our coffee tables? In this post I would like to introduce the subject of the DSS, and its influence on the Bible and Biblical studies. Then I will let Dr. VanderKam (who is indeed the expert) do the rest of the talking as I am linking his lecture at Andrews to this post. In 1946, along the hilly West Bank of the Dead Sea, a Bedouin shepherd boy was throwing rocks into random caves, as no doubt any child would do at that age, passing the time while his sheep grazed in a nearby field. He did this until he heard one of the rocks collide with something (perhaps ceramic) in one of the caves. Afterwards, the shepherd boy alerted his family and they inspected the cave, discovering seven scrolls and fragments in jars near the site of Qumran. As fantastic of a story this is, one would be surprised to know that most great archaeological finds begin in a similar fashion. This is the story of the discovery of Cave I. Since then eleven caves have been located in which the scribal community at Qumran hid their precious documents during the time of the Jewish Revolt in 68/69 CE. Who were these people? Why did they do such a thing? Dr. VanderKam has some interesting theories as to these people (so be sure to click the link to watch his lecture). Regardless of who or why, this archaeological discovery is no doubt perhaps one of the greatest in the history of "Biblical Archaeology" and Biblical studies. Before the discovery of the scrolls, the oldest Hebrew Text was the Masoretic Text (known as the MT in Biblical Studies) dating to the 10th Century CE. There were questions as to the reliability and transmission of such a text that has ancient claims when the earliest documents which survived are significantly late. Some would like to compare the transmission of the Bible to a game of "Telephone." An entertaining children's game where one child whispers a word or phrase and waits as it is whispered around the room, waiting to see the product of the transmission. Usually the end result is nothing compared to the word or phrase which began the game. In the same way, questions were raised concerning the continuous copying of the biblical text and over time, one would expect what we have in our Bibles to be different to what was originally written. However, after the discovery of the scrolls, the biblical texts found in the caves date as early as the 2nd Century BCE, almost a thousand years older than the MT! Scholars jumped at the possibility to examine the text to see if there were discrepancies and were baffled at the unusual accuracy of the texts compared to the Old Testament text we have today. One of the pioneers of Biblical Archaeology, William F. Arbright stated "We may rest assured that the consonantal text of the Hebrew Bible, though not infallible has been preserved with an accuracy perhaps unparalleled in any other Ancient Near Eastern literature." Of the scrolls, over 225 Biblical texts were found in the caves of Qumran. Other deuterocanical books recognized by the Catholic and Orthodox faiths were discovered such as the books of Tobit, Ben Sirach, Baruch 6 and Psalm 151. An entire Isaiah scroll (known as the Great Isaiah Scroll) was among the first seven scrolls discovered in Cave 1 and remains the only complete Biblical text and is on display at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem (shown above). This however is only the tip of the iceberg as this great discovery is still making waves today in Biblical Studies. Many books and articles have been published as to the results of intense analysis of these great scrolls and the community that may have preserved them. Why were they preserved? What purpose did they serve to their creators? Now is the time for me to step down and let Dr. VanderKam do the talking. Please watch his lecture and feel free to post comments and questions! Enjoy! Talmadge

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed